march 31 2022

je lis trop

dark night, red lights

I am always transfixed by the sight of a lonely car traveling in the night, slicing the darkness with its red lights. Whenever I’m confronted with such an image, I’m entirely pulled in, I can’t look away. I’ve seen it in movies (often in opening scenes), modern photography. Occasionally I’ve been such a traveler myself, looking at real nights and real streets. It’s a scene that suggests mystery, solitude, deviousness. I find it more mesmerizing than mountain ranges or meadows with flowers hovering above the green patches of land. So much meaning can be gleaned from it; at the same time, I see nothing.

My March pile

I thought about all of this while watching a group of people in the museum. Standing in front of a small, elegant painting - a serene landscape - they were whispering words of admiration to each other. It was a beautiful scene indeed. I was sitting next to a larger painting, thinking about pictures I found visually powerful, pictures with a magnetic pull, and I was arranging them all in my mind. Mountain ranges, meadows, scenes of people going about their ordinary business. But nothing could equal that one car and its red lights on a road. There is one book capable of evoking precisely the same atmosphere for me, and it’s ’s The Book of Disquiet. I’ve had this book in my reading list for good two years now – I was putting off reading it until some fitting time in the future (though I never knew when it would come). Last month, I finally acquired my copy.

“I want your reading of this book to leave you with the sense of having lived through some voluptuous nightmare”. The Book of Disquiet is full of beauty and hopelessness, disillusion and elegance. It is fragmented and reads like poetry, with rich images and sentences, where the reader inhales “ancient perfumes of rich satins”, can hear “murmurings of the birds”, observe “indefinite lucid blue pallor of the aquatic evening” and “sunsets in fateful skies”. Or simply sit with the narrator in the room, holding a cup of coffee, a cigarette, with “smoke of living wrapped about everything”. The Book of Disquiet repeats over and over again how there’s nothing that we can truly possess except for our dreams and thoughts. The outside world is just “an unaesthetic nightmare”. And it provides many examples on how to replace that world with dreaming, warns the reader to dream perfectly. It brushes off desires and hopes as “inelegant gestures”, praises discreetness and serenity and most importantly, mystery. The goal is “to organize our life so that it is a mystery to others”. And lastly – we should never forget that nothing has any meaning.

Flowers hovering above the street

Arranging books, gathering impressions

I believe this book merits rereading ten times before one can say, confidently, to have read it. The first time is just brushing the surface with fingertips. I would like to mull over those dreaming instructions, let the beautiful scenes unravel, appreciate every single word and detail, consider the absurdities and contradictions this book has to offer. I am still deciding whether it’s a poetic manual on life, dreaming, or writing. Despite the cold, despairing tone, there is so much light and hope within – marveling at the dawn and observing first hints of the morning while listening to the tram sounds, or relishing the atmosphere of lost kingdoms, or the warmth of childhood memories while sitting in a small, dusty office, surrounded by balance sheets.

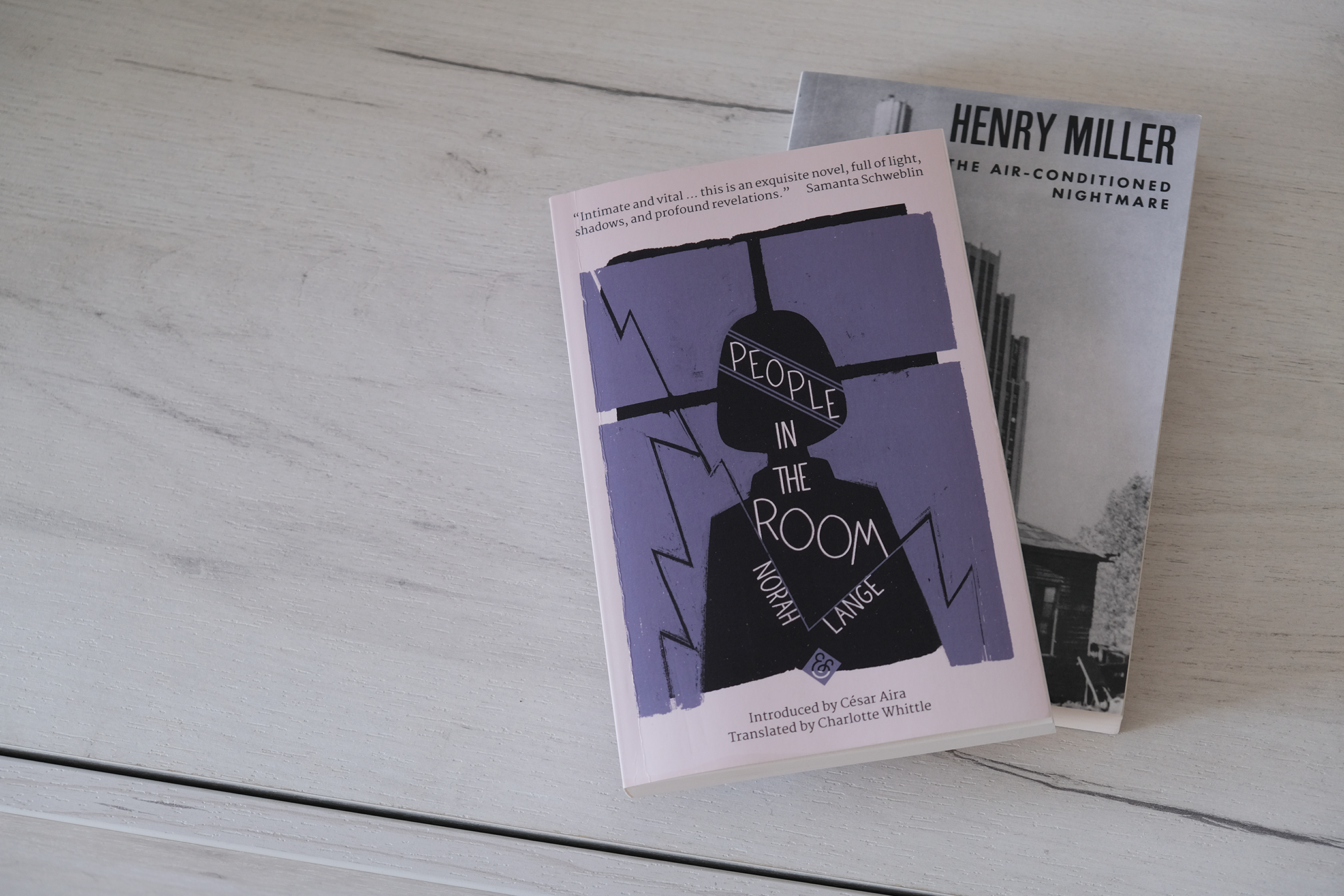

Reading Norah Lange and Henry Miller

Fernando Pessoa praised mystery, so did an Argentine writer , her works only now emerging from obscurity. In one of her interviews, she claimed that she could never be content with directness. Her 1950 novel People in the Room is fittingly enigmatic – scary, even, without my being able to understand nor explain why. It’s a story populated with ghosts, ambition, and longing. There are no moving cars nor red lights in it; not much motion in general, except for dark carriages advancing under the rain. An adolescent girl spends time in her drawing room and becomes gradually obsessed with three women across the street. She conjures up a whole world with imagined roles for them, tries to insert herself in their lives, become an active participant. There was a line in The Book of Disquiet, which was about seeing things “of which visibility cannot even conceive” – I think this was exactly what the story’s narrator was doing. She was possibly hallucinating all the things she’s telling us, but it is never clear what is real and what is simply a dream, a speculation. Upon closing the last page, I had an uneasy feeling, a feeling that sometimes stays with me when I reflect on my dreams in the morning – as if that something I experienced was too intense and too strange to be true.

White car in the evening

I wanted to place ’s The Air-Conditioned Nightmare next to Fernando Pessoa and Norah Lange, mostly because of the book’s title. I haven’t read this book yet, but the title alone suggests an image of a menacing road trip. Henry Miller sets out on a three-year long journey to describe his native land and see all the ways in which the man has divorced nature; it can possibly be a book about the triumph of mechanics over the meadows and green patches of land. But this is just my early interpretation. One more book I’d like to add is Lynch on Lynch by (edited by Chris Rodley). I’ve already read some fragments of it, a snippet of interview here or there. I am sure it is going to encapsulate absolutely everything I discussed above – mystery, dreams, and cars. Ever since I watched Mulholland Drive and Lost Highway, I’ve been thinking about these images, both appealing and saddening at the same time.